F ANNIE SPERRY (Part 1)

Cowgirl Queen of the Prickly Pear Valley

December 4, 2019

When Datus Sperry moved west with his family from New York State to the vicinity of Detroit, he may not have thought of a wife. When Rachel Schroeder had moved west from Germany with her family to the same neighborhood, she certainly had not thought of a husband, for she was just a baby, but Fate already had them cinched.

They met there, but the time was not yet right. Datus and brother, Myles, decided that Montana needed their exploring, and it was seven years before he got around to proposing by mail. Rachel, still available, was quickly aboard a train, and they married at Ft. Benton in 1879.

For a time they lived and Datus worked on the Nicholas Hilger ranch, on the Missouri River and around the Gates of the Mountains, but he and Rachel bought an abandoned homestead abutting Sleeping Giant Mountain, had a house built to replace the dugout that came with the property, and settled there to raise their five children. Carrie had been firstborn in 1881, and number four, Fannie, arrived in '87.

Rachel taught all her children to ride, but Fannie learned it best, and all the neighbors saw what a prodigy, what a magician with horses, the young girl was. At the same time, she was building a reputation as a sharpshooter.

Sister Carrie married Joe Hilger, son of Nicholas, who was another German immigrant and a man who came west to find gold, but failing at that, became a judge, and she eventually bore 13 children. The youngest of these was Viola, whom we twice visited and who provided interesting pictures and tales of the life of her celebrity aunt, who also had been her riding instructor.

One anecdote of Fannie's childhood concerned her mother, Rachel, out berry-picking when bitten by a rattlesnake and having to run home, because in the panic, the unreliable horses bolted. Not the prescribed treatment for a snakebite victim, but she reached the house, where Fannie compounded the bad therapy by administering a swig of alcohol, then made a life-saving ride to Helena for a doctor.

Another of Viola's recollections was of Fannie's employing her rifle to dispatch a bear that had come calling at the front door.

Still another, Viola remembered how her grandparents caught wild horses, had the children and ranch hands tame them, then augmented their income from their milking cows by selling the then-usable horses.

A neighbor had a wild critter, impossible to tame, so said all that had been bucked off. Fannie arrived on her mild little pony, and to the amazement of the trainers, offered a trade. The chaps eagerly accepted, then chuckled and asked her how she would get him home. She said she would ride him, then she jumped on the horse and did just that.

At sixteen Fannie was finished with school and pledged herself to a career of working with horses. She liked them high-spirited and fast and that summer, 1903, earned her first prize money by riding a big, bucking stallion. The crowd in nearby Mitchell were so taken by her that a hat was passed for her benefit, and thus was born a legend in rodeo and racing.

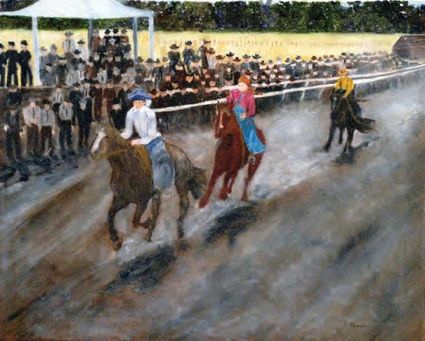

In his Wild West Show, Buffalo Bill had introduced what he called Pony Express Races. Modified in sundry ways, these came to be known in Montana as relay races, and while there were variations, a typical format was this: each competitor rode, say, four different horses, each mount going the same distance, with the rider's having to change at the completion of a length. For added excitement the contestant sometimes was required, as well, to saddle the next horse at high speed before flying off on the next lap. Some of these events ran over several days, each demanding a ride of several miles.

The races became popular ingredients of horse shows in Montana, and in 1904 Fannie raced professionally in Anaconda, Butte, Helena, and Missoula.

It is ironic that while women were fighting it out on the same ground as men, it was considered improper for women to spectate from the grandstands or whatever seating the venue offered. Rather, they sat caring for their children and picnicking and gossiping on surrounding hillsides.

Attendance at these rodeos could number into the thousands, and there were betting booths where the male fans could risk a few pesos on their favorite competitors.

After an initial season of that sport, Fannie established a pattern she followed throughout her career; returned to spend the winter working at whatever was her home at the time. At age 17, this was still the Sperry ranch, her parents' place.

The next Spring a promoter signed her to what she must have considered a fabulously lucrative contract for relay racing in the Midwest. He took three other young ladies of Fannie's acquaintance, and the "Montana girls" took to the relay racing circuit. The showman, in addition, insinuated some bucking horse contests into her duties.

Up to this era, women could ride only wearing a long skirt or dress, an impossible inconvenience for racing. Finally, someone created an outfit which looked like a modest skirt when one was standing, but was actually pantaloons with panels in front and back.

The following year the circuit expanded farther east, and bucking horse rides by Fannie Sperry became an ordinary adjunct to the races.

After the 1907 program their backer dissolved the team, and for the next five years she competed only in Montana. Her reputation had been firmly established, however, and she was invited to the first Calgary Stampede in 1912.

At that time there were two styles permitted to women bronc riders; one was the practice of hobbling the stirrups, which meant connecting them via a strap across the horse's belly. This effectively tied the rider to the saddle and reduced the chance of being thrown.

Fannie refused to adopt anything that lessened the challenge and also recognized the danger of being unable to dismount in an emergency. At least one rider death had been attributed to the practice, and Miss Sperry rode "slick and clean," as it was called; i.e., the men's way.

The favorite at Calgary was a Canadian girl, Goldie St. Clair, whose first successful ride, a gem, was on a horse that had thrown a man to his death a week before. On her last ride, Fannie drew the same horse, won the competition with a performance that dazzled the audience, and became the "Ladies' Bucking Horse Champion of the World!"

Upon her triumphant return to the Sperry ranch she brought a $1000 prize, which she donated to the family, and a solid gold belt buckle. She was in demand at fairs and horse shows, and, at Deer Lodge, at least one man took notice of her as more than a tenacious, gritty bronc rider – as a woman, in fact.

He was Bill Steele, ten years older than she, a local cow-puncher, an occasional contestant, but better recognized as a rodeo clown. Despite what seem limited attractions, Fannie fell for him, they married in April, 1913, and immediately joined – what else? – a Wild West Show.

That year it was Winnipeg that staged a rodeo extravaganza, and Mrs. Steele again left Canada as women's world champion of the bucking horse.

After that winter they formed their own show and traveled across Montana as far as Miles City. It was in this tour, while demonstrating her facility with horses that were fast or unwilling to be ridden, she developed her marksmanship into an act with her husband.

Among other tricks, Bill was able to display his trust in his wife by holding in his fingers china eggs that she shattered with her rifle.

He was also so bold as to clench smoking cigars in his mouth and allow Fannie to flick off the ashes with bullets. Cigarettes would have been more exciting, but audiences were delighted with cigars, which were likely more comfortable for Bill, anyway.

Reader Comments(0)